Adaptation Planning

Adapting to disturbances (whether, they are extreme events or continuous gradual changes) requires identifying appropriate actions that reduce and/or manage a community’s vulnerability to long term consequences from such disturbances. While some of these consequences may be physical in nature, many of them may also be socio-economic, cultural, and political. When communities are able to anticipate significant disturbances, prepare for them, respond to them, and recover from them with least damage to their environment, social well-being, and economy, then they are poised to be resilient. Hence, local communities and governments need to be able to plan for strategies that minimize their risks and maximize their resilience by adjusting how resources, operations, and assets are managed, before or at the onset of such disturbances. It is important to note that strategies may include a variety of approaches – some that are hard (e.g., building new infrastructure) and some that are soft (e.g., raising awareness and education, change in insurance support, low impact technologies, etc.).

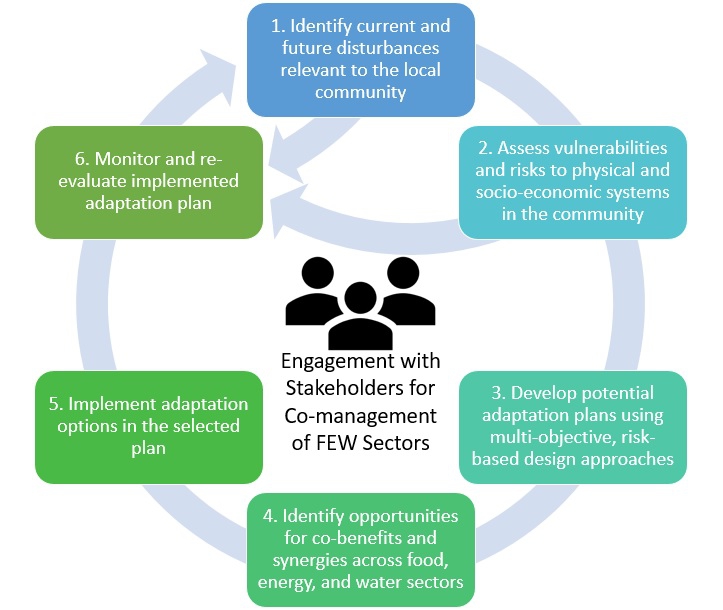

When planning for adaptation in communities with interconnected food, energy, and water (FEW) sectors, interdependencies between all sectors should be taken into consideration when costs and benefits of adaptation actions are estimated. For long term investments in adaptation actions involving water resources, energy resources, and land resources, communities should also consider how intergenerational equity, cultural, environmental, and other socio-economic factors influence costs and benefits across geographic and temporal scale. A well-executed adaptation planning process allows decision makers to organize, evaluate, prioritize, and select from a portfolio of diverse adaptive management strategies that are appropriate for their region. The range of strategies that are identified can then be communicated to other stakeholders and lawmakers for gathering support for co-management and implementing on-the-ground decisions. Figure 1 illustrates the overall approach to an adaptation planning process, one in which stakeholder engagement and coordination is central to all planning steps.

Engagement of stakeholders with different background and interests is critical to adaptation planning. This is especially important because for many types of disturbances (e.g., climate change) we currently don’t have top-level (e.g., national and state level) institutions and bridging organizations that (a) facilitate integrated adaptation planning across multiple sectors and across multiple spatial and temporal scales, (b) provide financial resources to multiple sectors to jointly enact actions over a long period of time, and (c) coordinate communication among sectors (NRC 2009, 2010). In addition, fluctuations in economic cycles and political volatility make it additionally challenging to create appropriate top-level institutions that can consistently fund and garner political support over longer periods of time. Hence, bottom-up partnerships that involve grassroots efforts by local stakeholders (e.g., those representing the local FEW sectors) and local institutions in communities can act as catalysts for engaging top-level institutions in creating new, cross-scale, financial, infrastructure, and policy mechanisms that are co-managed by multiple parties (Berkes, 2002) . Such cross-scale partnerships increases the likelihood of local communities adopting or “buying into” recommended actions, and ensuring that parties have mechanisms for sharing responsibilities, costs, and risks of adaptation in an uncertain and changing world. Hence, engagement with stakeholders at different levels is extremely critical when navigating through all of the steps of the adaptation planning process, so that opportunities and synergies can be identified to fill in the gaps and empower communities to take control of their future.